Saturday, December 23, 2006

Tuesday, December 19, 2006

I am so excite!!!!

Idea for a post: parody of a celebrity-style greenroom blog entry ("I'm here waiting to go on Leno and I'm soooo excited!") about my current wait to appear before grad committee.

1:05 pm.

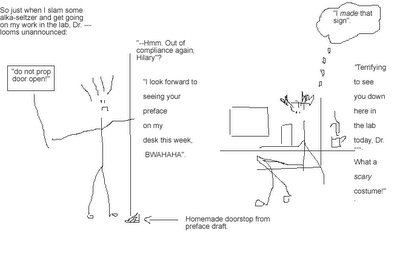

Current location: Eating a cookie with green frosting while waiting in the lab to appear before grad committee.

On "ipod": Bach F minor concerto for piano v. orchestra.

1:06 pm.

Oh my god, your whole mouth is green. How am I going to explain that to grad committee?

1:07 pm

Gasp. Sarah L. has been called before the committee, ps, leaving her cookies unguarded.

1:08 pm

There goes Myrtle.

1:09 pm

Omg, it took me like forever to perfect my cartoon elevator.

So what you have is like a basic cartoon elevator that you can modify and resave?

1:05 pm.

Current location: Eating a cookie with green frosting while waiting in the lab to appear before grad committee.

On "ipod": Bach F minor concerto for piano v. orchestra.

1:06 pm.

Oh my god, your whole mouth is green. How am I going to explain that to grad committee?

1:07 pm

Gasp. Sarah L. has been called before the committee, ps, leaving her cookies unguarded.

1:08 pm

There goes Myrtle.

1:09 pm

Omg, it took me like forever to perfect my cartoon elevator.

So what you have is like a basic cartoon elevator that you can modify and resave?

Thursday, December 14, 2006

son of god

"There", said Hilary, wrapping the last string of holiday lights around an elephant-shaped murti.

Woot sub 1

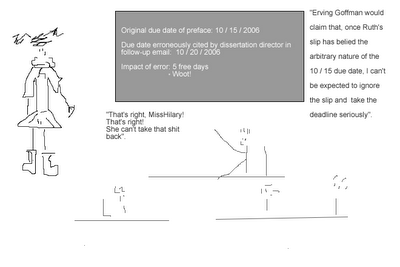

Date: Thu 14 Dec 15:31:49 EST 2006

From: Ross Pudaloff Add To Address Book | This is Spam

Subject: Meeting, Dec. 19

To: schandra@wayne.edu, "Frances J. Ranney", cschmitt@wayne.edu, shaviro@shaviro.com, Elizabeth Sklar , Barrett Watten , at4592@wayne.edu, az8578@wayne.edu, Myrtle Hamilton , aa1236@wayne.edu

Cc: r.burgoyne@wayne.edu, slabeau@wayne.edu, ab0128@wayne.edu, ag9521@wayne.edu

Dear Everyone,

We've received a second preface and list (Hilary Ward's), which you will find in your mailboxes.

So, the agenda for Tuesday's meeting is as follows:

1:00-1:45: Discussion and review of Sarah Delhousse's Preface and List.

1:45-2:30: Discussion and review of Hilary Ward's Preface and List.

Ross

From: Ross Pudaloff

Subject: Meeting, Dec. 19

To: schandra@wayne.edu, "Frances J. Ranney"

Cc: r.burgoyne@wayne.edu, slabeau@wayne.edu, ab0128@wayne.edu, ag9521@wayne.edu

Dear Everyone,

We've received a second preface and list (Hilary Ward's), which you will find in your mailboxes.

So, the agenda for Tuesday's meeting is as follows:

1:00-1:45: Discussion and review of Sarah Delhousse's Preface and List.

1:45-2:30: Discussion and review of Hilary Ward's Preface and List.

Ross

Wednesday, December 13, 2006

...

Every time I turn around, I remind myself to retreat into the blinding white silent inside of my mind and say no, no, no, that's not how it happened. "It" varies as a function of time.

Sunday, December 10, 2006

woot

Hilary Anne Ward

Qualifying Examination Preface

Qualifying Exam Committee: Drs. Frances Ranney and Ruth Ray [Dirs.], Dr. Ellen Barton.

December 10, 2006

The history of technical communication is primarily a history of writing at work. Since its inception as a writing course within the engineering department of agricultural and mechanical (A&M) colleges founded by the Morrill Act (1862; 1877), technical communication has struggled to attain legitimacy as an academic field by positing theories, methodologies, pedagogies and ethics that “can be applied to the workplace” (Anderson, p. online). When the first technical writing courses began within engineering departments in 1908, the term technical writing referred to the workplace writing of engineers; the corresponding “Engineering English” courses emphasized “the usefulness of English in advancing the professional practice” of engineering (Harabager, 1938, p. 157). Then, as the Taylor system of “scientific” management (1895-1947) lead to fine-grained specialization in the engineering workplace, including the separation of clerical and managerial from manual labor, technical writing differentiated from engineering and grew into an aspiring communications profession comparable to radio broadcasting and journalism (Longo, 2000, p. 123). The academic field of technical communication instituted graduate-level courses to support the profession; after World War II, technical communication programs had migrated from engineering departments to the Rhetoric and Compositions programs within English departments in which technical communication is new most often housed (Connors, p. 178-188). This new milieu of English studies sparked a “humanistic” (Miller, 1979) approach to the research and practice of technical communication; this humanistic approach turned away from its original emphasis on precise representations of technical data to focus more broadly on technical writing as an act of participation in a scientific community – a rhetorical act of participation laden with ethical (Ornatowski, 1992; Katz, 1992), political (Longo, 2000; Kynell, 2000) and theoretical (Dobrin, 1989) implications. While this humanistic approach certainly has “broadened our understanding” of the role of technical communication in shaping technical knowledge, subsequent research has focused exclusively on humanistic aspects of technical communication in one setting: the workplace (see, for example, Doheny-Farina, 1988; Dombrowski, 1994; Winsor, 2003).

After the surge of critical and reflective historical studies in the early 1990s (Russell, 1991; Adams, 1993; Kynell, 1996), the exclusive emphasis on the workplace in technical communication has become a focus of occasional critique. Four researchers have proposed the examination of new, non-workplace sites: Tebeaux’ (1997) historical research analyzes women’s domestic technical writing in the English renaissance, with a focus on the professional status of midwifery; Kynell and Savage (2003) calls for an examination of technical writing in “alternative” workplaces such as contractor-client relationships and home offices (p.4); Kimball (2006), who ventures furthest from the workplace context, calls for research of extra-institutional documentation in “dangerous” cases such as computer hacking, fraud, and terrorism manuals (p. 84). However, with the exception of Tebeaux, whose historical investigation of the professional status of midwifery and on the working conditions of midwives retains obvious ties to the traditional emphasis on workplace studies in technical communication (Tebeaux, 1999), these calls for research in non-workplace sites remain unanswered: no actual archival or empirical research in technical communication has ventured outside of the workplace into new and “dangerous” sites.

One particularly striking consequence of the exclusive emphasis on the workplace in technical communication is that technical communication is one of few remaining fields in the social sciences that have yet to develop underlife as a legitimate area of study. The term underlife refers to communicative acts that “employ unauthorized means, or obtain unauthorized ends, or both” to undercut prescribed organizational norms and is associated with an early move in sociology research to examine off-the-record or “deviant” communication in organizations (Goffman, Asylums, p. 189). In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the fields that “nourish” technical communication (Johnson, p. 13) such as composition studies (Brooke, 1987), literacy studies (Beall and Trimbur, 1993; Moje, 2000) and industrial-organizational sociology (Goffman; White, 1983) began to investigate forms of underlife that are found within, or are related to, more traditional research sites: graffiti as a literacy practice of gang-connected youth (Moje) , note-passing and other off-topic communication in a Composition course (Brooke) and the strategies that private neighborhoods employ to undercut municipal social policies (White). Research from within the computer and information sciences suggests that computer users enjoy a rich and multifaceted underlife of quasi-legal and illegal hacking activities that force a computer system perform functions that the system “was not originally designed to do” (Thomas, 2001, p. ii); technical knowledge about how to execute these hacking activities is documented in the form of hacks, or informal instructions written by hackers. These instructions are then published on the Worldwide Web (WWW) to fulfill the hacker ethic of technical knowledge that is “free from subordination to commodity production” (Wark, par. 31) and to obtain prestige for the hacker. However, despite the availability of the hacks and the central role of hacks in sustaining hacking activities and hacker culture, the exclusive emphasis on the workplace in technical communication has discouraged the field from researching hacks and other potentially significant forms of underlife in technical writing.

This QE list and preface, then, will prepare me to develop a dissertation project that broadens the scope of technical communication research (Dobrin, 1987) to include technical writing underlife. More specifically, I plan to describe and analyze hacks as an emerging genre of computer documentation. The corpus for analysis will consist of web pages tagged as “hack” on del.icio.us, an online bookmarking system that allows users to tag widely used sources on a given keyword and relevant commentary. This selection method will allow me to focus on hacks that circulate widely and generate reader responses. Two complementary methods will guide the textual analysis of the corpus: a genre analysis of the structures, stylistic features and content of the hacks (Swales, p. 27) and a discourse analysis of interesting features of the hacks (Barton and Stygall; Bazerman and Prior; Hyland). Finally, discourse-based interviews with hack authors, readers and authors of commentary will provide contextual information about the communicative purposes of the hacks, their intended audiences, and the actual situations in which hacks are composed and interpreted (Bazerman and Prior, 2004). This analysis of hacks directly responds to recent calls for technical communication research in new, non-workplace sites (Tebeaux; Savage; Kimball) as well as to Johnson’s (1998) call to broaden technical communication scholarship in the area of computer documentation by examining informal documentation written by users (p. 121). Furthermore, an analysis of hacks will promote the ideal of interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary research in technical communication (Johnson, p. 14) by participating in underlife studies, an area of interest for surrounding fields. Finally, on a broader social level, an analysis of hacks will illuminate the role of networked writing in promoting and sustaining hacking, an activity that has been the target of highly publicized legal and technological countermeasures such as the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) (1986; 1999) and the USA Patriot Act of 2001, which augmented the penalties and scope of the CFAA.

The first section of the list, technical communication, surveys historical perspectives and current research in the field. Most of these histories have emerged within the past 15 years. Historical accounts by Russell (1991) and Adams (1993) focus on the emergence of technical writing as an academic discipline, with Kynell (1996) focusing more specifically on the relationship between technical communication and engineering programs. These disciplinary histories are supplemented by historical accounts of the practice of technical communication in the workplace (see, for example, Tebeaux, 1997). A survey of research in the field of technical communication complements these historical accounts; foundational texts on the list examine nonacademic writing as a broad research area (Odell and Goswami, 1985), technical and professional communication as a focus within nonacademic writing (Bazerman and Paradis, 1991), and technical communication as a distinct emphasis (Anderson, Brockmann and Miller, 1993). More recent edited collections critique and theorize the foundational texts (Kynell, 1999; Mirel and Spilka, 2002), while Windsor (1996) and Sauer (1996) and draw on this emerging body of knowledge to provide book-length research studies of technical communication at particular workplace sites. As Aldred (1997) acknowledges, scholarly historical and research studies are woefully incomplete if not read alongside practitioner-oriented texts. Therefore, the scholarly texts listed above are supplemented by practitioner-oriented handbooks such as Jordan’s (1971) early handbook of technical writing and recent works by Schriver (1997), Tufte (1997) and Doheny-Farina (1998) that apply technical communication research and theory to the practice of technical communication.

The second section of the list, Computers and Composition, provides a review of research on technology and writing situated within the broader context of Rhetoric and Composition Studies. This established body of research informs conversations about technology and writing within technical communication (Selber, 1997). First, a selection of texts on the list comprise an overview of the rhetorical tradition that underlies composition studies (Aristotle, 1950; Bizell and Herzberg, 1990; Foss, 1990; Poulakos, 1993) and the history of Composition Studies as an academic discipline (Harris, 1997; Crowley, 1998; Vitanza, 1997). Next, foundational texts in Computers and Composition Studies explore the theoretical and practical implications of writing with technology for Composition Studies, raising issues such as technology use in differing social contexts , changing conceptions of “literacy” in a digital age (Selber, 2004) and the impact of specific writing environments such as MOOs and networked classrooms on the composing process (Holmevick and Haynes, 1998; Johnson-Eilola, 1996 ). Drawing on research from within Computers and Composition Studies, Sullivan and Dautermann (1996) and Selber (1997) initiate a conversation about computers and writing from within the discipline of technical communication. While technical communication as an academic discipline has contributed only two (2) books to the area of technology and writing, practitioner-oriented texts have grappled with the exigencies of technology and writing in the workplace. Handbooks by Berk and Devlin (1991) and Britton and Glynn (1989) and address writing with technology at work, with an emphasis on technical and professional writing in high-tech organizations.

The third area of the list, technology and culture, will help me to position my dissertation in the field of technical communication within wider theoretical and philosophical perspectives on technology. While technology and culture is a broad research area comprising cultural studies, technology studies and media studies, this list focuses on readings in technology and culture that are widely read and cited within technical communication. Ellul (1964) provides a theoretical perspective on technology as part of la technique, or “the totality of methods rationally arrived at and having absolute efficiency (for a given stage of development) in every field of human activity” (p. xxv). Ellul’s controversial perspective on technology is extensively discussed – and critiqued—by theorists in diverse fields related to technical communication. In philosophy and political theory, Winner (1997) highlights the human constraints that can, and should, limit technological innovation; Feenberg offers a similar critique of technological determinism from the perspective of Marxist critical theory; Mitcham (1998) calls for a philosophical inquiry into the technical and humanistic nature of technology. In contrast to these theoretical and philosophical perspectives on technology and culture, Latour and Woolgar (1986) pioneer empirical work on technology and culture, focusing on the networks of human and nonhuman actors that work to “construct” everyday reality. Latour's and Woolgar's empirical work sparked a succession of studies on the interrelationship of technologies, cultures and data: Pinch and Bijker (1987; 1992) investigate the historical and cultural processes that socially construct technological systems; Nardi and O'Day's (2000) workplace ethnography discovers “information ecologies” or local, interwoven systems of technology, humans and information, while Doheny-Farina (1996) explores the shifting relationships that link electronic communities and geophysical neighborhoods. Finally, drawing on both the theoretical conversation sparked by Ellul and the empirical approach of Latour and Woolgar, Johnson-Eilola's Datacloud (1996) proposes new forms of technical communication and documentation that are designed to support “recently emerging forms of work” (p. 1).

The final section of the list, qualitative methods, provides an overview of the capabilities and limitations of a qualitative approach to social sciences research. Readings in this section will help me in conceptualizing and designing a project, conducting research within the site and reporting findings (Becker, 1998; Cresswell, 2003; Deznin and Lincoln, 2000; Gubrium and Holstein, 1997). As the primary methods text, Swales' Genre Analysis (1994) introduces methods for analyzing generic features of texts; more recent works by Swales update and expand on these methods (Swales, 2000; Swales, 2004). These texts on genre analysis are complemented by other relevant qualitative methods for textual analysis, such as discourse analysis of written texts (Barton and Stygall, 2002; Hyland, 2000; Bazerman and Prior, 2004) and Geisler’s (2003) methods for analyzing texts mediated by networked information technologies. While the general methods texts address a wide range of qualitative approaches including contextual research, two texts on the list focus exclusively on this area: Emerson, Fretz and Shaw’s (1995) Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes provides a guide to complex process of ethnographic research, while Hine’s (2000) Virtual Ethnography introduces methods for conducting ethnographic research in online spaces.

Qualifying Examination Preface

Qualifying Exam Committee: Drs. Frances Ranney and Ruth Ray [Dirs.], Dr. Ellen Barton.

December 10, 2006

The history of technical communication is primarily a history of writing at work. Since its inception as a writing course within the engineering department of agricultural and mechanical (A&M) colleges founded by the Morrill Act (1862; 1877), technical communication has struggled to attain legitimacy as an academic field by positing theories, methodologies, pedagogies and ethics that “can be applied to the workplace” (Anderson, p. online). When the first technical writing courses began within engineering departments in 1908, the term technical writing referred to the workplace writing of engineers; the corresponding “Engineering English” courses emphasized “the usefulness of English in advancing the professional practice” of engineering (Harabager, 1938, p. 157). Then, as the Taylor system of “scientific” management (1895-1947) lead to fine-grained specialization in the engineering workplace, including the separation of clerical and managerial from manual labor, technical writing differentiated from engineering and grew into an aspiring communications profession comparable to radio broadcasting and journalism (Longo, 2000, p. 123). The academic field of technical communication instituted graduate-level courses to support the profession; after World War II, technical communication programs had migrated from engineering departments to the Rhetoric and Compositions programs within English departments in which technical communication is new most often housed (Connors, p. 178-188). This new milieu of English studies sparked a “humanistic” (Miller, 1979) approach to the research and practice of technical communication; this humanistic approach turned away from its original emphasis on precise representations of technical data to focus more broadly on technical writing as an act of participation in a scientific community – a rhetorical act of participation laden with ethical (Ornatowski, 1992; Katz, 1992), political (Longo, 2000; Kynell, 2000) and theoretical (Dobrin, 1989) implications. While this humanistic approach certainly has “broadened our understanding” of the role of technical communication in shaping technical knowledge, subsequent research has focused exclusively on humanistic aspects of technical communication in one setting: the workplace (see, for example, Doheny-Farina, 1988; Dombrowski, 1994; Winsor, 2003).

After the surge of critical and reflective historical studies in the early 1990s (Russell, 1991; Adams, 1993; Kynell, 1996), the exclusive emphasis on the workplace in technical communication has become a focus of occasional critique. Four researchers have proposed the examination of new, non-workplace sites: Tebeaux’ (1997) historical research analyzes women’s domestic technical writing in the English renaissance, with a focus on the professional status of midwifery; Kynell and Savage (2003) calls for an examination of technical writing in “alternative” workplaces such as contractor-client relationships and home offices (p.4); Kimball (2006), who ventures furthest from the workplace context, calls for research of extra-institutional documentation in “dangerous” cases such as computer hacking, fraud, and terrorism manuals (p. 84). However, with the exception of Tebeaux, whose historical investigation of the professional status of midwifery and on the working conditions of midwives retains obvious ties to the traditional emphasis on workplace studies in technical communication (Tebeaux, 1999), these calls for research in non-workplace sites remain unanswered: no actual archival or empirical research in technical communication has ventured outside of the workplace into new and “dangerous” sites.

One particularly striking consequence of the exclusive emphasis on the workplace in technical communication is that technical communication is one of few remaining fields in the social sciences that have yet to develop underlife as a legitimate area of study. The term underlife refers to communicative acts that “employ unauthorized means, or obtain unauthorized ends, or both” to undercut prescribed organizational norms and is associated with an early move in sociology research to examine off-the-record or “deviant” communication in organizations (Goffman, Asylums, p. 189). In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the fields that “nourish” technical communication (Johnson, p. 13) such as composition studies (Brooke, 1987), literacy studies (Beall and Trimbur, 1993; Moje, 2000) and industrial-organizational sociology (Goffman; White, 1983) began to investigate forms of underlife that are found within, or are related to, more traditional research sites: graffiti as a literacy practice of gang-connected youth (Moje) , note-passing and other off-topic communication in a Composition course (Brooke) and the strategies that private neighborhoods employ to undercut municipal social policies (White). Research from within the computer and information sciences suggests that computer users enjoy a rich and multifaceted underlife of quasi-legal and illegal hacking activities that force a computer system perform functions that the system “was not originally designed to do” (Thomas, 2001, p. ii); technical knowledge about how to execute these hacking activities is documented in the form of hacks, or informal instructions written by hackers. These instructions are then published on the Worldwide Web (WWW) to fulfill the hacker ethic of technical knowledge that is “free from subordination to commodity production” (Wark, par. 31) and to obtain prestige for the hacker. However, despite the availability of the hacks and the central role of hacks in sustaining hacking activities and hacker culture, the exclusive emphasis on the workplace in technical communication has discouraged the field from researching hacks and other potentially significant forms of underlife in technical writing.

This QE list and preface, then, will prepare me to develop a dissertation project that broadens the scope of technical communication research (Dobrin, 1987) to include technical writing underlife. More specifically, I plan to describe and analyze hacks as an emerging genre of computer documentation. The corpus for analysis will consist of web pages tagged as “hack” on del.icio.us, an online bookmarking system that allows users to tag widely used sources on a given keyword and relevant commentary. This selection method will allow me to focus on hacks that circulate widely and generate reader responses. Two complementary methods will guide the textual analysis of the corpus: a genre analysis of the structures, stylistic features and content of the hacks (Swales, p. 27) and a discourse analysis of interesting features of the hacks (Barton and Stygall; Bazerman and Prior; Hyland). Finally, discourse-based interviews with hack authors, readers and authors of commentary will provide contextual information about the communicative purposes of the hacks, their intended audiences, and the actual situations in which hacks are composed and interpreted (Bazerman and Prior, 2004). This analysis of hacks directly responds to recent calls for technical communication research in new, non-workplace sites (Tebeaux; Savage; Kimball) as well as to Johnson’s (1998) call to broaden technical communication scholarship in the area of computer documentation by examining informal documentation written by users (p. 121). Furthermore, an analysis of hacks will promote the ideal of interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary research in technical communication (Johnson, p. 14) by participating in underlife studies, an area of interest for surrounding fields. Finally, on a broader social level, an analysis of hacks will illuminate the role of networked writing in promoting and sustaining hacking, an activity that has been the target of highly publicized legal and technological countermeasures such as the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) (1986; 1999) and the USA Patriot Act of 2001, which augmented the penalties and scope of the CFAA.

The first section of the list, technical communication, surveys historical perspectives and current research in the field. Most of these histories have emerged within the past 15 years. Historical accounts by Russell (1991) and Adams (1993) focus on the emergence of technical writing as an academic discipline, with Kynell (1996) focusing more specifically on the relationship between technical communication and engineering programs. These disciplinary histories are supplemented by historical accounts of the practice of technical communication in the workplace (see, for example, Tebeaux, 1997). A survey of research in the field of technical communication complements these historical accounts; foundational texts on the list examine nonacademic writing as a broad research area (Odell and Goswami, 1985), technical and professional communication as a focus within nonacademic writing (Bazerman and Paradis, 1991), and technical communication as a distinct emphasis (Anderson, Brockmann and Miller, 1993). More recent edited collections critique and theorize the foundational texts (Kynell, 1999; Mirel and Spilka, 2002), while Windsor (1996) and Sauer (1996) and draw on this emerging body of knowledge to provide book-length research studies of technical communication at particular workplace sites. As Aldred (1997) acknowledges, scholarly historical and research studies are woefully incomplete if not read alongside practitioner-oriented texts. Therefore, the scholarly texts listed above are supplemented by practitioner-oriented handbooks such as Jordan’s (1971) early handbook of technical writing and recent works by Schriver (1997), Tufte (1997) and Doheny-Farina (1998) that apply technical communication research and theory to the practice of technical communication.

The second section of the list, Computers and Composition, provides a review of research on technology and writing situated within the broader context of Rhetoric and Composition Studies. This established body of research informs conversations about technology and writing within technical communication (Selber, 1997). First, a selection of texts on the list comprise an overview of the rhetorical tradition that underlies composition studies (Aristotle, 1950; Bizell and Herzberg, 1990; Foss, 1990; Poulakos, 1993) and the history of Composition Studies as an academic discipline (Harris, 1997; Crowley, 1998; Vitanza, 1997). Next, foundational texts in Computers and Composition Studies explore the theoretical and practical implications of writing with technology for Composition Studies, raising issues such as technology use in differing social contexts , changing conceptions of “literacy” in a digital age (Selber, 2004) and the impact of specific writing environments such as MOOs and networked classrooms on the composing process (Holmevick and Haynes, 1998; Johnson-Eilola, 1996 ). Drawing on research from within Computers and Composition Studies, Sullivan and Dautermann (1996) and Selber (1997) initiate a conversation about computers and writing from within the discipline of technical communication. While technical communication as an academic discipline has contributed only two (2) books to the area of technology and writing, practitioner-oriented texts have grappled with the exigencies of technology and writing in the workplace. Handbooks by Berk and Devlin (1991) and Britton and Glynn (1989) and address writing with technology at work, with an emphasis on technical and professional writing in high-tech organizations.

The third area of the list, technology and culture, will help me to position my dissertation in the field of technical communication within wider theoretical and philosophical perspectives on technology. While technology and culture is a broad research area comprising cultural studies, technology studies and media studies, this list focuses on readings in technology and culture that are widely read and cited within technical communication. Ellul (1964) provides a theoretical perspective on technology as part of la technique, or “the totality of methods rationally arrived at and having absolute efficiency (for a given stage of development) in every field of human activity” (p. xxv). Ellul’s controversial perspective on technology is extensively discussed – and critiqued—by theorists in diverse fields related to technical communication. In philosophy and political theory, Winner (1997) highlights the human constraints that can, and should, limit technological innovation; Feenberg offers a similar critique of technological determinism from the perspective of Marxist critical theory; Mitcham (1998) calls for a philosophical inquiry into the technical and humanistic nature of technology. In contrast to these theoretical and philosophical perspectives on technology and culture, Latour and Woolgar (1986) pioneer empirical work on technology and culture, focusing on the networks of human and nonhuman actors that work to “construct” everyday reality. Latour's and Woolgar's empirical work sparked a succession of studies on the interrelationship of technologies, cultures and data: Pinch and Bijker (1987; 1992) investigate the historical and cultural processes that socially construct technological systems; Nardi and O'Day's (2000) workplace ethnography discovers “information ecologies” or local, interwoven systems of technology, humans and information, while Doheny-Farina (1996) explores the shifting relationships that link electronic communities and geophysical neighborhoods. Finally, drawing on both the theoretical conversation sparked by Ellul and the empirical approach of Latour and Woolgar, Johnson-Eilola's Datacloud (1996) proposes new forms of technical communication and documentation that are designed to support “recently emerging forms of work” (p. 1).

The final section of the list, qualitative methods, provides an overview of the capabilities and limitations of a qualitative approach to social sciences research. Readings in this section will help me in conceptualizing and designing a project, conducting research within the site and reporting findings (Becker, 1998; Cresswell, 2003; Deznin and Lincoln, 2000; Gubrium and Holstein, 1997). As the primary methods text, Swales' Genre Analysis (1994) introduces methods for analyzing generic features of texts; more recent works by Swales update and expand on these methods (Swales, 2000; Swales, 2004). These texts on genre analysis are complemented by other relevant qualitative methods for textual analysis, such as discourse analysis of written texts (Barton and Stygall, 2002; Hyland, 2000; Bazerman and Prior, 2004) and Geisler’s (2003) methods for analyzing texts mediated by networked information technologies. While the general methods texts address a wide range of qualitative approaches including contextual research, two texts on the list focus exclusively on this area: Emerson, Fretz and Shaw’s (1995) Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes provides a guide to complex process of ethnographic research, while Hine’s (2000) Virtual Ethnography introduces methods for conducting ethnographic research in online spaces.

current affirmations

The list is done and formatted [# of sources = 124. Current weight: 114].

[breathe]

The references are done and formatted.

[breathe]

I will soon attain release from this endless cycle of revision.

[breathe]

The methods section is standing between me and a fine bottle of Boone's farm.

[breathe].

[breathe]

The references are done and formatted.

[breathe]

I will soon attain release from this endless cycle of revision.

[breathe]

The methods section is standing between me and a fine bottle of Boone's farm.

[breathe].

sometimes

Sometimes you didn't really love the person and sometimes you "didn't really love the person". Then I gently freed the scarf from the door but no one moved.

the end is near

This analysis of hacks directly responds to recent calls for technical communication research in new, non-workplace sites (Tebeaux; Savage; Kimball) as well as to Johnson’s (1998) call to broaden technical communication scholarship in the area of computer documentation by examining informal documentation written by users (p. ). Furthermore, an analysis of hacks will promote the ideal of interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary research in technical communication (Johnson, p. 14) by participating in underlife studies, an area of interest for surrounding fields.

Saturday, December 09, 2006

sample paragraph with blur

A particularly striking consequence of the narrow emphasis on the workplace in technical communication is that technical communication is the only field in the social sciences that has yet to develop underlife as a legitimate area of study. The term underlife refers to communicative acts that “employ unauthorized means, or obtain unauthorized ends, or both” to undercut prescribed organizational norms (Asylums, p. 189) and is associated with an early move in sociology research to examine off-the-record or “deviant” communication in organizations (cite Goffman). In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the fields that “nourish” technical communication (Johnson, p. 13) such as composition studies (Brooke, 1987), literacy studies (Beall and Trimbur, 1993; Moje, 2000) and industrial-organizational sociology (White, 1983) began to investigate forms of underlife that are found within, or are related to, more traditional research sites: list examples. Explain hackers and hacks with Bob as implied imaginary reader [cf fjr’s advice]. Incorporate the phrase “cooperate interdisciplinarily with” to show that TC is a big loser for its failure to join in.

sample paragraph at angle

After the surge of critical and theoretical studies in the early 1990s, the narrow emphasis on the workplace in technical communication has become the occasional focus of critique. Three researchers have proposed the examination of new, non-workplace sites: Tabeaux’ (cite) historical research analyzes women’s domestic technical writing in the English renaissance, with a focus on the professional status of midwifery; Savage (2003) calls for an examination of technical writing in “alternative” workplaces such as contractor-client relationships and home offices; Kimball, who ventures furthest from the workplace context, calls for research of extra-institutional documentation in “dangerous” cases such as computer hacking, fraud, and terrorism manuals [p. 2 -- check]. However, with the exception of Tabeaux, whose historical investigation of the professional status of midwifery and on the working conditions of midwives retains obvious ties to the traditional emphasis on workplace studies in technical communication, these calls for research in non-workplace sites remain unanswered: no actual historical or empirical research in technical communication has ventured outside of the workplace into new and “dangerous” sites.

sample paragraph

Hilary Anne Ward

English 9990: Preparation for the QE

The history of technical communication is primarily a history of writing at work. Since its inception as a writing course within the engineering department of agricultural and mechanical (A&M) colleges founded by the Morrill Act (1862; 1877), technical communication has struggled to attain legitimacy as an academic field by positing theories, methodologies, pedagogies and ethics that “can be applied to the workplace” (Anderson). When the first technical writing courses began within engineering departments in 1908, the term technical writing referred to the workplace writing of engineers; the corresponding “Engineering English” courses emphasized “the usefulness of English in advancing the professional practice” of engineering (Harabager). Then, as the Taylor system of “scientific” management (1895-1947) lead to fine-grained specialization in the engineering workplace, including the separation of clerical and managerial from manual labor, technical writing differentiated from engineering and grew into an aspiring communications profession comparable to radio broadcasting and journalism [cite Longo]. The academic field of technical communication instituted graduate-level courses to support the profession; after World War II, technical communication programs had migrated from engineering departments to the Rhetoric and Compositions programs within English departments in which technical communication is new most often housed (Connors).

English 9990: Preparation for the QE

The history of technical communication is primarily a history of writing at work. Since its inception as a writing course within the engineering department of agricultural and mechanical (A&M) colleges founded by the Morrill Act (1862; 1877), technical communication has struggled to attain legitimacy as an academic field by positing theories, methodologies, pedagogies and ethics that “can be applied to the workplace” (Anderson). When the first technical writing courses began within engineering departments in 1908, the term technical writing referred to the workplace writing of engineers; the corresponding “Engineering English” courses emphasized “the usefulness of English in advancing the professional practice” of engineering (Harabager). Then, as the Taylor system of “scientific” management (1895-1947) lead to fine-grained specialization in the engineering workplace, including the separation of clerical and managerial from manual labor, technical writing differentiated from engineering and grew into an aspiring communications profession comparable to radio broadcasting and journalism [cite Longo]. The academic field of technical communication instituted graduate-level courses to support the profession; after World War II, technical communication programs had migrated from engineering departments to the Rhetoric and Compositions programs within English departments in which technical communication is new most often housed (Connors).

the research library makes me mad

One thing that makes me mad is when my favorite sources at the Kresge research library "disappear" onto a high-surveillance shelving cart behind the desk. And I have to write down the names and call numbers for all the books because the girl behind the desk goes "What?".

to do:

#1 Develop a full draft of the preface [Saturday]#2 Fully revise the full draft of the preface [Saturday]

#3 Fully revise the narration of the list [Sunday]

#4 Fully revise the list [Sunday]

#5 Create a Works Cited page [Sunday}

#6 Draw on advanced list-making and narration skills to compose and circulate holiday wish list to friends and family.

*Italicized tasks are miraculously finished despite off-task web surfing and multiple panicked emails about the status of the 10th floor microwave.

#3 Fully revise the narration of the list [Sunday]

#4 Fully revise the list [Sunday]

#5 Create a Works Cited page [Sunday}

#6 Draw on advanced list-making and narration skills to compose and circulate holiday wish list to friends and family.

*Italicized tasks are miraculously finished despite off-task web surfing and multiple panicked emails about the status of the 10th floor microwave.

Friday, December 08, 2006

some preface

The history of technical communication is primarily a history of writing at work. Since its inception as a writing course within the engineering department of agricultural and mechanical (A&M) colleges founded by the Morrill Act (1862; 1877), technical communication has struggled to attain legitimacy as an academic field by positing theories, methodologies, pedagogies and ethics that “can be applied to the workplace” (Anderson). When the first technical writing courses began within engineering departments in 1908, the term technical writing referred to the workplace writing of engineers; the corresponding “Engineering English” courses emphasized “the usefulness of English in advancing the professional practice” of engineering (Harabager).

Wednesday, December 06, 2006

website launch itinerary

#4 Champagne.

To aid with smooth application of reindeer ears onto setup crew.

To aid with smooth application of reindeer ears onto setup crew.

Friday, December 01, 2006

blot

Due to the fact that Aveda dyes tend to romanticize their shades (ie, my natural hair color is "espresso"), it strikes me as particularly insulting that my fantasy ash / wheat mix is officially named "drab".

Have they never *seen* a girl with cool skin tones sporting those trendy golden highlights? It looks, oh maybe not drab, but ghastly, and plus she's overcompensating.

You see, the problem here is that that girl would never be caught dead in a color named "drab".

Have they never *seen* a girl with cool skin tones sporting those trendy golden highlights? It looks, oh maybe not drab, but ghastly, and plus she's overcompensating.

You see, the problem here is that that girl would never be caught dead in a color named "drab".

...

"Maybe if I stand here and wait, another answer will come" Hilary mused doubtfully, watching the snowflakes plummet to their death.

She traced the mandala of a hand turkey in the frost on the window and the snowflakes danced among the noncompossible worlds.

She traced the mandala of a hand turkey in the frost on the window and the snowflakes danced among the noncompossible worlds.

Tuesday, November 28, 2006

Sunday, November 26, 2006

Going down?

I courteously pressed the button on the North Side elevators, inviting him to plummet to his death.

current stats a la bloggerandme

preface: um

weight: well...

hair: no

fave food: churros

fave color: ash

pet peeve: trendily shortened words

point of style: incredibly vain monk

weight: well...

hair: no

fave food: churros

fave color: ash

pet peeve: trendily shortened words

point of style: incredibly vain monk

S

AND STOP ADDING AN S WHERE PERHAPS AN S SHOULD NOT BE! I added in a kind of mythical silent scream.

after all:

To remain responsive to other disciplines as well as relevant to the wider culture milieu of technology and society, technical writing research must find new and refreshing ways of investigating its core object of study: technical writing.

why I could not write my....

google search terms during my "research hour" :

cool chocolate brown + highlights + almond

cool chocolate brown + highlights + almond

Monday, November 13, 2006

Sunday, November 12, 2006

new

Hilary was surprised to note that the had started losing interest in people even before they could actualize their potential to annoy her.

Friday, November 10, 2006

Thursday, November 09, 2006

....?

That's not who I said, I said. I said Kim, Kim, Kim.

And the plate of fries wavered. Quiet!, I added, glaring at Sharon.

And the plate of fries wavered. Quiet!, I added, glaring at Sharon.

Thursday, November 02, 2006

Tuesday, October 31, 2006

Friday, October 27, 2006

Thursday, October 26, 2006

news and announcements

Tuesday, October 24, 2006

Friday, October 20, 2006

it's dark outside again

This gap in technical communication’s interdisciplinary history reveals an underlying disconnect between technical communication theory, which posits a fluid and interdisciplinary field, and our tacit knowledge that technical communication is inextricably tied to “industrial settings” (Savage, p. 3) .

and the wind blew and the snow snowed

However, as fictionalized accounts with the persuasive goal of claiming territory and power, these mainstream disciplinary histories are inherently incomplete: “we tend to avoid unseemliness when telling familial stories” (Ianetta and Fredal, p. 186). Indeed, while the story of technical communication as a historically interdisciplinary field smoothes over our “persistent disagreements” about the “knowledge domain” of technical communication (Savage, p. 21), technical communication has not always functioned “interdisciplinarily”.

Thursday, October 19, 2006

writing....

In “Surveying the stories we tell: English, communication, and the rhetoric of our surveys of rhetoric”, Ianetta and Fredal (2006) point out that disciplinary histories are not objective records but “fictionalized accounts” that “engage questions of territoriality and power” (p. 186). While Ianetta and Fredal’s survey focuses on disciplinary histories of rhetoric, their observations also apply to the history of technical communication – a history that, as Savage notes in the preface to Power and Legitimacy in Technical Communication, “is in the very early stages of being written” (p. 4).

While technical communication has existed as an academic discipline since its inception as [deal with this crap about the Morrill act later], no “important” or widely circulating disciplinary history emerged until the early 1990s: Connors’ The Rise of Technical Writing Instruction in America, Russell’s (1991) Writing in the Academic Disciplines, 1870-1990, Adams’ (1993) A History of Professional Writing Instruction in American Colleges, Kynell’s (1994) Writing in the Milieu of Utility.

Like the histories of rhetoric reviewed by Ianetta and Fredal, these emerging histories of technical communication are “shaped by the tensions inherent in disciplinary status” (p. 186); put in more concrete terms, histories of technical communication must prove that an area once associated with “wretched” writing, “younger faculty members or various fringe people” and “professional suicide” has “truly” attained “a state of efficiency and productive professionalism”(p. 192).

As with all “fictionalized accounts”, disciplinary histories sometimes dwell on noble themes to “overlook the current situation” and “dwell instead on a glorious and regal past” (p. 186). Like the histories of rhetoric reviewed by Ianetta and Fredal, disciplinary histories of technical communication “meditate” on one recurring theme: the “expansive interdisciplinarity” of the discipline (p. 186). According to the mainstream historical narrative, technical communication always “functions interdisciplinarily” (Johnson, p. 14), drawing on research strategies and methods from other scholarly fields associated with technology and communication. Insert quotes from the sources listed above.

The (his)tory of technical communication as an interdisciplinary field provides an overarching explanation for the field’s unseemly “paradoxes, disagreements and contradictions” , and accounts for both technical communication’s “strong and penetrating perspective” [Johnson, p. 14] and its enduring “identity crisis” [Johnson-Eilola, cite].

However, it does not matter whether the authors praise or blame interdisciplinarity in any given historical account; as Ianetta and Fredal note, the scholarly discussion of interdisciplinarity lends “metatheoretical sophistication” to a discipline that [insert a statement about tech comm’s theoretical naivete].

However, these mainstream disciplinary histories are always incomplete: they smooth over “indelicacies”, concealing gaps, contradictions and silences. While the story of technical communication’s interdisciplinary history sparks “critical self-reflection” (cite) to explain the “persistent disagreements” about the “knowledge domain” of technical communication (Savage, p. 21) , technical communication has not always functioned “interdisciplinarily”.

For example, in the late 1980s and early 1990s – the same era in which the mainstream histories emerged – the disciplines that “nourish” technical communication developed a new emphasis : underlife studies. Drawing on Goffman’s work on underlife in public institutions from sociology research two decades earlier, the disciplines of organizational sociology (cite), literacy studies (cite) and composition began to investigate “insert quote”. However, despite the fact that technical communication is closely allied to these disciplines [rephrase this] and despite Brooke’s observation that “insert quote”, technical communication has not developed a corresponding emphasis in underlife as an area of research. Viswaswaran notes that [insert quote about attending to silences] ; as [name of reviewer] says about [the one guy who never wrote about underlife when anthropologists were studying it] , technical communication’s neglect of underlife is not “merely accidental” (p).

While technical communication has existed as an academic discipline since its inception as [deal with this crap about the Morrill act later], no “important” or widely circulating disciplinary history emerged until the early 1990s: Connors’ The Rise of Technical Writing Instruction in America, Russell’s (1991) Writing in the Academic Disciplines, 1870-1990, Adams’ (1993) A History of Professional Writing Instruction in American Colleges, Kynell’s (1994) Writing in the Milieu of Utility.

Like the histories of rhetoric reviewed by Ianetta and Fredal, these emerging histories of technical communication are “shaped by the tensions inherent in disciplinary status” (p. 186); put in more concrete terms, histories of technical communication must prove that an area once associated with “wretched” writing, “younger faculty members or various fringe people” and “professional suicide” has “truly” attained “a state of efficiency and productive professionalism”(p. 192).

As with all “fictionalized accounts”, disciplinary histories sometimes dwell on noble themes to “overlook the current situation” and “dwell instead on a glorious and regal past” (p. 186). Like the histories of rhetoric reviewed by Ianetta and Fredal, disciplinary histories of technical communication “meditate” on one recurring theme: the “expansive interdisciplinarity” of the discipline (p. 186). According to the mainstream historical narrative, technical communication always “functions interdisciplinarily” (Johnson, p. 14), drawing on research strategies and methods from other scholarly fields associated with technology and communication. Insert quotes from the sources listed above.

The (his)tory of technical communication as an interdisciplinary field provides an overarching explanation for the field’s unseemly “paradoxes, disagreements and contradictions” , and accounts for both technical communication’s “strong and penetrating perspective” [Johnson, p. 14] and its enduring “identity crisis” [Johnson-Eilola, cite].

However, it does not matter whether the authors praise or blame interdisciplinarity in any given historical account; as Ianetta and Fredal note, the scholarly discussion of interdisciplinarity lends “metatheoretical sophistication” to a discipline that [insert a statement about tech comm’s theoretical naivete].

However, these mainstream disciplinary histories are always incomplete: they smooth over “indelicacies”, concealing gaps, contradictions and silences. While the story of technical communication’s interdisciplinary history sparks “critical self-reflection” (cite) to explain the “persistent disagreements” about the “knowledge domain” of technical communication (Savage, p. 21) , technical communication has not always functioned “interdisciplinarily”.

For example, in the late 1980s and early 1990s – the same era in which the mainstream histories emerged – the disciplines that “nourish” technical communication developed a new emphasis : underlife studies. Drawing on Goffman’s work on underlife in public institutions from sociology research two decades earlier, the disciplines of organizational sociology (cite), literacy studies (cite) and composition began to investigate “insert quote”. However, despite the fact that technical communication is closely allied to these disciplines [rephrase this] and despite Brooke’s observation that “insert quote”, technical communication has not developed a corresponding emphasis in underlife as an area of research. Viswaswaran notes that [insert quote about attending to silences] ; as [name of reviewer] says about [the one guy who never wrote about underlife when anthropologists were studying it] , technical communication’s neglect of underlife is not “merely accidental” (p).

...

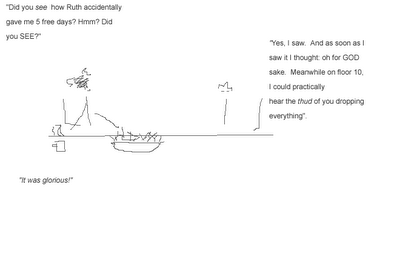

Did you get my phone message? Asked Sarah L. urgently.

No.

Did you see?, she said, pointing to the computer screen.

Yeah. So?

Hasn't graduate school taught you anything about close reading, she stammered and began to read aloud with the thud of her hand punctuating every word.

No.

Did you see?, she said, pointing to the computer screen.

Yeah. So?

Hasn't graduate school taught you anything about close reading, she stammered and began to read aloud with the thud of her hand punctuating every word.

Wednesday, October 18, 2006

bad news -- updated

A montage of email headers ranked least to most ominous:

Date: Mon 3 Apr 17:25:35 EDT 2006

From: Royanne Smith Add To Address Book | This is Spam

Subject: Classroom Observation

To: Hilary_anne@wayne.edu

Cc: lbrill@wayne.edu

Date: Thu 19 Oct 17:25:42 EDT 2006

From: Margaret Maday Add To Address Book | This is Spam

Subject: Boiler Project - 5057 Woodward

To: EVERYONE-SO-FAR@lists.wayne.edu

Date: Fri 7 Apr 10:21:37 EDT 2006

From: Katie Gutowski Add To Address Book | This is Spam

Subject: DO NOT USE STAIRWELL

To: EVERYONE-SO-FAR@LISTS.WAYNE.EDU

Date: Tue 6 Sep 17:01:31 EDT 2005

From: Margaret Maday Add To Address Book | This is Spam

Subject: Extra Students

To: EVERYONE-SO-FAR@LISTS.WAYNE.EDU

Date: Mon 3 Apr 17:25:35 EDT 2006

From: Royanne Smith

Subject: Classroom Observation

To: Hilary_anne@wayne.edu

Cc: lbrill@wayne.edu

Date: Thu 19 Oct 17:25:42 EDT 2006

From: Margaret Maday

Subject: Boiler Project - 5057 Woodward

To: EVERYONE-SO-FAR@lists.wayne.edu

Date: Fri 7 Apr 10:21:37 EDT 2006

From: Katie Gutowski

Subject: DO NOT USE STAIRWELL

To: EVERYONE-SO-FAR@LISTS.WAYNE.EDU

Date: Tue 6 Sep 17:01:31 EDT 2005

From: Margaret Maday

Subject: Extra Students

To: EVERYONE-SO-FAR@LISTS.WAYNE.EDU

Tuesday, October 17, 2006

doom

Date: Tue 17 Oct 12:28:19 EDT 2006

From: "dissertation advisor" ab0128@wayne.edu Add To Address Book | This is Spam

Subject: QE preface and list

To: HILARY WARD ag9521@wayne.edu

Cc: "other advisor" ae8683@wayne.edu

Hi Hilary: Can we expect to find your revised preface and list in our

mailboxes this Friday? I'm feeling the need for some stimulating

reading over the weekend.

From: "dissertation advisor" ab0128@wayne.edu Add To Address Book | This is Spam

Subject: QE preface and list

To: HILARY WARD ag9521@wayne.edu

Cc: "other advisor" ae8683@wayne.edu

Hi Hilary: Can we expect to find your revised preface and list in our

mailboxes this Friday? I'm feeling the need for some stimulating

reading over the weekend.

Monday, October 16, 2006

Saturday, October 14, 2006

just motivating myself to revise...

Hilary Anne Ward

English 9990: Preparation for the Qualifying Exam

QE preface—draft

Sept. 13, 2006

Both as a research field and as a professional practice, the history of technical communication “is in the very early stages of being written” (Savage, p. 4). In the early 1990s, histories of technical communication as an academic discipline began to appear with Russell (1991), Adams (1993), Kynell (1994) and Rivers (1999) contributing the most “important” or widely read and cited historical accounts (Kynell and Moran, p. 1). While these historical accounts vary in scope and focus, a common thread in the mainstream historical narrative is the conclusion that technical communication “functions interdisciplinarily” (Johnson, p. 14), drawing on research strategies and methods from other scholarly fields associated with technology and communication. The authors of these histories use the story of technical communication as an interdisciplinary field, in turn, to explain both technical communication’s “strong and penetrating perspective” [Johnson, p. 14] and its enduring “identity crisis” [Johnson-Eilola, cite].

English 9990: Preparation for the Qualifying Exam

QE preface—draft

Sept. 13, 2006

Both as a research field and as a professional practice, the history of technical communication “is in the very early stages of being written” (Savage, p. 4). In the early 1990s, histories of technical communication as an academic discipline began to appear with Russell (1991), Adams (1993), Kynell (1994) and Rivers (1999) contributing the most “important” or widely read and cited historical accounts (Kynell and Moran, p. 1). While these historical accounts vary in scope and focus, a common thread in the mainstream historical narrative is the conclusion that technical communication “functions interdisciplinarily” (Johnson, p. 14), drawing on research strategies and methods from other scholarly fields associated with technology and communication. The authors of these histories use the story of technical communication as an interdisciplinary field, in turn, to explain both technical communication’s “strong and penetrating perspective” [Johnson, p. 14] and its enduring “identity crisis” [Johnson-Eilola, cite].

and

I think I am in love with everyday life. This morning I felt a twinge of sadness on seeing my checkered blouse for the last time in the hamper, then cheered up in anticipation of finally seeing the blouse on someone who can wear light green.

2007 ATTW proposal

Title: 2007 ATTW proposal

By: Hilary

While professionals exert social control by positioning themselves “as the sole providers of vital, knowledge-based services” (Faber, 2006, p. 315), recent work in professional communication suggests that this “professional dominance” (Faber, p. 322) is not absolute. Medical patients, for example, deploy a range of “discursive” and “bodily” countermeasures to “resist medical regulatory rhetoric” (Koeber, p. 87). However, no scholarly work has examined how these acts of “rhetorical agency and resistance” (p. 87), in turn, impact and change the “mainstream medical discourse” (Koeber, p. 93).

This paper, then, examines the impact of patients’ networked writing on one form of change in the mainstream medical discourse: depathologization, the process by which medical pathologies are reclassified as neutral traits. As virtual communities of individuals with a common medical diagnosis emerge over wide-area networks [WANs], these communities gradually break away from the medical community to establish a community identity that is not based on a medical-pathological model. These new communities are then poised to argue for depathologization.

I will examine the role of networked writing in the depathologization of several virtual communities, focusing on how the networked writing of the autism community has transformed mainstream medical discourse about autism as reflected in recent moves from within mainstream medical discourse to depathologize autism (Attwood, 2006).

By: Hilary

While professionals exert social control by positioning themselves “as the sole providers of vital, knowledge-based services” (Faber, 2006, p. 315), recent work in professional communication suggests that this “professional dominance” (Faber, p. 322) is not absolute. Medical patients, for example, deploy a range of “discursive” and “bodily” countermeasures to “resist medical regulatory rhetoric” (Koeber, p. 87). However, no scholarly work has examined how these acts of “rhetorical agency and resistance” (p. 87), in turn, impact and change the “mainstream medical discourse” (Koeber, p. 93).

This paper, then, examines the impact of patients’ networked writing on one form of change in the mainstream medical discourse: depathologization, the process by which medical pathologies are reclassified as neutral traits. As virtual communities of individuals with a common medical diagnosis emerge over wide-area networks [WANs], these communities gradually break away from the medical community to establish a community identity that is not based on a medical-pathological model. These new communities are then poised to argue for depathologization.

I will examine the role of networked writing in the depathologization of several virtual communities, focusing on how the networked writing of the autism community has transformed mainstream medical discourse about autism as reflected in recent moves from within mainstream medical discourse to depathologize autism (Attwood, 2006).

Monday, October 09, 2006

Thursday, October 05, 2006

use of foreshadowing

"Hwaet: So the new TAs took one look at me and wrote me off: What's she doing here? And no one bothers me for sage advice in the office.

So new girl 1 says / oh no, I lost my key.

New girl 2 replies / they probably have a spare one in the main office that you can use for today.

Oh good, says new girl 1 / who would I see about that.

I don't know says new girl 2 / but I think her name is like Margaret M--

But what do I know, you know, so I didn't say nothing."

So new girl 1 says / oh no, I lost my key.

New girl 2 replies / they probably have a spare one in the main office that you can use for today.

Oh good, says new girl 1 / who would I see about that.

I don't know says new girl 2 / but I think her name is like Margaret M--

But what do I know, you know, so I didn't say nothing."

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)